by Jędrzej Janicki & Wioletta Kazimierska-Jerzyk (24.01.2021)

At least one of the artistic achievements of the author of this poster is well known to everyone who in the years 1962-1973 at 19:20 sat down in front of the TV and with flushed faces waited for the broadcast of the next episode of the first Polish bedtime story entitled Jacek i Agatka (Little Jack and Agathy).

Fig. 1. Stamp issued by the Polish Post on August 30, 1975 in connection with the popularization of the social idea

construction of the Monument-Hospital of the Children's Health Center. Series with catalog numbers 2245-2248, see Catalog of postage stamps, photo: WKJ (author's collection)

Yes, yes, two nice puppets, voiced in a funny way by actress Zofia Raciborska, were designed by Adam Kilian. This somewhat tiresome and intrusively moralizing fairy tale by Wanda Chotomska, however, became a kind of symbol of "children's entertainment" of those times and thanks to two faces painted on balls made of lathed beech wood, Kilian himself survived in the memory of subsequent generations[1].

Fig. 2. Jacek i Agatka, Polish Television, 1962–1973, screenplay by Wanda Chotomska, stage design by Adam Kilian

There is no doubt that Kilian is one of the most important artists directing his works at children – not only as a set designer for plays and animated films and as a designer of characters and costumes but also as an illustrator. This is clearly emphasized by the latest publications devoted to the authors of book illustrations. Many of the artist's works are distinguished by a special interpenetration and sometimes inversion of different worlds: real and fairy-tale, adult and children's, serious and funny. As noted by Anita Wincencjusz-Patyna, Kilian “shaped his characters in book illustrations in the likeness of theatre puppets, and naturally gave the presented world the character of stage design”[2]. On the other hand, as Barbara Gawryluk describes it, his house was also a studio and it was completely open to children, while the theatre was a second home for the whole family[3]. From generation to generation, theatre and visual arts lived there. His mother, Janina Kilian-Stanisławska, had a great influence on the development of the artist's creative path. She possessed an extraordinary biography. Before the war she dealt with art theory and criticism, writing, for example, for the Lviv magazine Świat Kobiecy (Woman’s World) and later for the monthly Teatr (Theatre). She devoted the period of her later creative activity to the development of puppet theatre in Poland[4]. The second person who had a significant influence on Kilian was painter and logician Leon Chwistek. It was he who sustained the love for children's art instilled in the young artist by his mother and he who organized the first exhibition of Kilian’s works[5]. Kilian himself illustrated over fifty books for children and in 1956 he created, perhaps now even more associated with his name than Jacek i Agatka, great ascetic folk (seemingly irreconcilable task) illustrations for Hanna Januszewska's book Pyza na polskich dróżkach (Pyza on Polish Paths).

However, life may be perverse, because the described poster has almost nothing to do with children's aesthetics... It promotes the play Lilla Weneda staged by the Arlekin Puppet Theatre in Łódź, which had its premiere on December 2, 1966. It's like a puppet show, but it is a spectacle for adults – not the first and not the last one at Arlekin. Henryk Ryl, the director of this play and the then artistic director of the theatre, perceived Lilla Weneda as a warning reminding us of the monstrous history of World War II. As he wrote, “we must not forget those times – if only for them never to be repeated in our lives. Let them go to the cruel and bloody legend, but at the same time already distant and irretrievable”[6]. Thus, Ryl was trying to swear his war experiences into a legend metaphorically told by this very spectacle based on Juliusz Słowacki's work. For Kilian, it was the first of nine stage set designs made for Arlekin.

History is dark and painful, so it's no wonder that the poster has a similar atmosphere. The main motif of the composition is the depiction of a harp in which a mysterious figure is inscribed. It is probably the king of Wends Derwid – imprisoned and crying tears of blood. The hero's despair and the drama of his people are reflected in the terribly sad eyes, so suggestively captured by Kilian in the convention of a raw woodcut technique. The fact that this figure is somehow "imprisoned" in the harp refers not only to Derwid, but also to the title character. In Słowacki's work, the instrument became a symbol of both hope for survival and loss itself. However, the author does not overly dazzle with the means of artistic expression (though Słowacki’s work may be tempting for such solutions). Kilians’s manner is here subdued and precise. A similar style, made in the woodcut technique or inspired only by it, was used by Kilian in many book projects (e.g. Legenda o Liczyrzepie, Pieśń Swantibora, or the masterfully published miniature Dawna Polska w anegdocie by Maria and Władysław Tomkiewicz), but he skilfully adapted it to the character of the given tragedy. The poster is brutally complemented by a bloody-red stain in the right hand bottom side, which serves as a background for basic information about the performance. We can only guess to what extent Kilian's intention was to make the outline of this patch resemble the post-war territory of Poland...

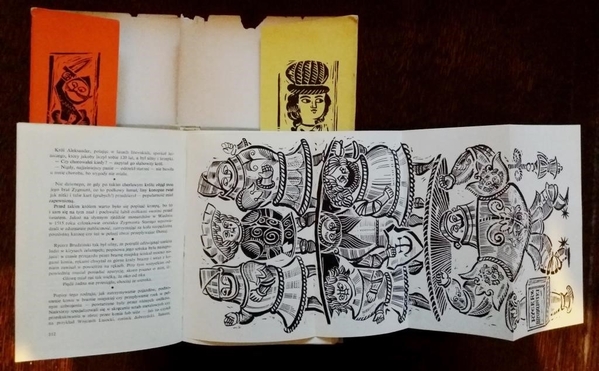

Fig. 3. Maria & Władysław Tomkiewiczow, Dawna Polska w anegdocie [Old Poland in an anecdote],

illustrated by Adam Kilian, Wiedza Powszechna, Warszawa 1973, p. 112.

Joanna Kilian, the artist's daughter, recalls that "his [Kilian’s – J. J., W.K.J], studio at home was a bit like a cabinet of curiosities”[7]. And the poster itself is also a bit like that. However, if we look into the programme booklet and the leaflet, we will see other woodcuts depicting characters and props from the performance, including the lovely Lilla Weneda, whose figure is framed in a floor-length hair border[8]. We will be surprised by the ingenuity in processing folk motifs and techniques, thanks to which these works gain a modern decorative character. Of course, Kilian departs very far from the then triumphant assumptions propagated by the admirers of the Polish School of Posters. However, if we pay attention to the freedom of the line, the ornament that does not yield to a rigorous rhythm and the various ways of escaping from realism, we will notice that Kilian similarly strives for his creative autonomy.

[1] Barbara Gawryluk, Radość tworzenia. Adam Kilian, in: B. Gawryluk, Ilustratorki i ilustratorzy. Motylki z okładki i smoki bez wąsów, Wydawnictwo Marginesy, Warszawa 2019, p. 239.

[2] Anita Wincencjusz-Patyna, Teatralia, in: Admirałowie wyobraźni. 100 lat polskiej ilustracji dla dzieci, edited by Anita Wincencjusz-Patyna Wydawnictwo Dwie Siostry, Warszawa 2020, p. 382.

[3] Barbara Gawryluk, Radość tworzenia…, pp. 243–244.

[4] See Janina Kilian-Stanisławska’s bio: http://www.encyklopediateatru.pl/autorzy/4543/janina-kilian-stanislawska.

[5] The exhibition was held in 1930s, Barbara Gawryluk, Radość tworzenia…, p. 242.

[6] Henryk Ryl, Krok naprzód, in: Lilla Weneda [programme booklet of the spectacle], Państwowy Teatr Lalek „Arlekin” Łódź 1966, unnumbered pages.

[7] Barbara Gawryluk, Radość tworzenia…, p. 244.

[8] Henryk Ryl, Krok naprzód, in: Lilla Weneda [program book of the spectacle], Państwowy Teatr Lalek „Arlekin” Łódź 1966, unnumbered pages. The program book and the leaflet of the spectacle can be downloaded here: https://e-teatr.pl/files/programy/51179/lilla_weneda_teatr_arlekin_lodz_1966.pdf.